A series of articles to reflect my thoughts on old age

Collecting Holy Things

The Yiddish writer, Israel Leib Peretz, spins the tale of a soul whose admittance to the World to Come is conditional on returning to this world and locating objects of religious interest which will resolve a dilemma of heaven’s own making. You see, the scales determining the soul’s fate are so finely balanced between its good deeds and its misdemeanors, that the heavenly court is unable to reach a decision on the soul’s eternal destination: Gan Eden or Gehenna; heaven or hell. Inevitably, there is a queue, and the administering angels are under pressure. Rather than take up more heavenly time, the soul is dispatched to garner evidence, in the shape of three gifts, which will tilt the scales in its favour.

The neshamah, the soul, flies hither and thither in its search and, over a span of years, collects the items that, hopefully, will realize its salvation: some grains of soil from the Land of Israel, a common pin of the sort that women used to secure their hats to their hair with, and a kippah. Each object bloodied by the martyrdom of a Jewish woman or man for the sake of their faith. One by one the items are presented on high and accepted, and the soul is permitted to enter the gate of heaven.

I, too, am a collector of holy things. Not, you can be assured, relics of martyrdom: that would be too grisly. Rather, humble offerings which could be tendered as unsolicited gifts, if (heaven forfend!) I were to find myself in a predicament akin to that of the soul in Peretz’s story.

My first submission would be a yellowing page torn from the Jewish Chronicle of July 16th, 1943. At the foot of the page there is a photo of my cousin, Sylvia, Corporal S Fenton, from the Mile End Road, in the uniform of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force who has been Mentioned in Dispatches and listed in the King’s Birthday Honours. Sylvia only joined the forces because, in her own words, ‘life in the East End was so bloody boring’, but her logistical work on bomb loads in Bomber Command helped lay the foundation of an Allied victory which, together with the resultant liberation of the survivors of the Shoah from the camps, merits her a degree of holiness on a par with that of a Tsaddik. Sylvia died a few years ago, aged 97, her resilient spirit unbroken. She would have had no problem gaining admittance at the pearly gates. And her experience of logistics, doubtless, has been put to good use in the day-to-day administration of heaven.

Growing up in Stamford Hill, most of the boys I was friendly with came from families who were not especially observant. Sure, we went to cheder during the week and shul on Shabbos, but we also found our way to Arsenal or Tottenham on Saturday afternoon. However, there was one family who were noted for their frumkeit, though, it must be said,their sons, who attended the same secular school as the rest of us, never behaved as though they were a cut above us. It so happened that the father of this family took a bus to and from work – in the nineteen fifties who could afford a car? During the winter months, when Shabbos came in early, he did not always get home before dusk. Now, what I witnessed was this: at the time his bus was due, his wife would be waiting for him at the bus stop. As he alighted, they embraced and walked home arm in arm as darkness enveloped them. For the wife, even the Sabbath had to concede to her sense that her rightful place was with her man. If anyone was to condemn her husband for breaking the sanctity of the day, let them condemn her too. Stooping, I retrieve the discarded bus ticket: my second gift.

Languishing in the bottom drawer of my desk is a photograph of a 1930’s group of smartly dressed youngish Jewish women, stalwarts of the Princess of Wales Lodge Number 25, a friendly society whose raison d’etre in those far off pre-welfare state days was to provide support in times of sickness and unemployment to its members. Seated in the front row are the movers and shakers adorned with sashes of office. Among them, the third woman on the left, bespectacled, in a black dress with a lace top, is my mother, Rachel Finestein. She wears the collar of her past presidency. The friendly society depended on the scrupulous honesty of its elected honorary officers in collecting subscriptions and distributing benefits to those in need. My mother donated her presidential collar to the archive of the United Jewish Friendly Society where it remains to this day in storage at the University of Southampton. As an invisible soul, I would have little trouble gaining access and filching the artefact for the purpose of my supplication of the heavenly tribunal. The third gift to be presented on High.

A page from the JC, a discarded bus ticket, a presidential collar. Armed with my holy gifts, my preparations are complete. Maybe they won’t be necessary, and my soul will attain its seat in paradise on its own merits. But, in the event of the scales being hung, the verdict handed down to Peretz’s fictional soul would suffice: ‘Truly beautiful gifts, unusually beautiful. …… They have no practical value, no use at all, but as far as beauty is concerned – unusual’.

Here’s what I did since my cancer diagnosis

In June 2020, discovering that I was unable to pee, I was rushed to Barnet General Hospital, by my wife, where my bladder was drained via the insertion of a catheter. Indescribable relief.

Having read my medical record on computer, the A&E medic, who treated me, patted me on the arm and told me I was a good man. Which started alarm bells ringing; good man is the stuff of funeral orations. Subsequently, I was advised that I had stage 3 prostate cancer: a growth was also present in organs adjacent to my prostate.

Age 73, I was working as an ESOL lecturer at Barnet and Southgate College. My diagnosis and the requirement to attend hospital consultations nudged me into resigning my post at the end of the academic year.

Uncertainty about the future made it prudent for us to downsize. Six months into retirement we moved from a 3/4 bedroom semi-detached in Edgware to a two-bedroom maisonette in Stanmore: a town where folk smile and exchange a good morning as strangers pass in the park.

Meanwhile, my ongoing treatment at the Royal Free in Hampstead was successful in limiting the spread of the disease, crucially by reducing my PSA to near zero. I was warned there would be side effects: constant hot flushes being the least; a small price to pay for staying alive.

Time to swim with dolphins? Ascend Kilimanjaro? Take a world cruise? Pray at the Wall? The idea of a bucket list had little appeal. True, we treated ourselves to a trip to the USA, to attend our grandson’s bar mitzvah, but otherwise our choice was to remain on these shores where my wife, Sonia, and I were embedded in our small world of friends and community.

Humdrum? Possibly. But contentment assumes many guises….

I got the idea of a Singing Circle from YouTube. A Jerusalem ensemble called Nava Tehillah had fired my enthusiasm. Their appearance at Limmud Conference knocked my socks off. I would establish an offshoot: the Hebrew songsters of Edgware. Starting with a small nucleus of around five, we have now grown to thirty regulars. I rapidly discovered that songs from the shows and the hits of yesteryear were preferred by most of our singers to the Book of Psalms, the stock in trade of Nava Tehillah. Readjusting my vision was not an issue; we still have the likes of Erev Shel Shoshanim and Tzenah Tzenah in our repertoire of 250 songs.

In truth, we are the not quite good enough club; some of us have been ejected from choirs, others have only just learned to shed their fear of singing in a public space. Thanks to a friend, who has sung with event bands, we have been drilled into a disciplined acapella group. My role is to prepare the programme for our weekly sessions, and to manage the bookings. Bookings? We are taking them up to February 2025. The secret of our success? We have become a circle of friends supporting each other though widowhood, Alzheimer’s and the many other issues which beset the 70 plusses. There is real joy in what we do. Having coffee in a break from rehearsals seals the bonds of camaraderie. Dressing up for a performance is beyond exciting.

Getting in the saddle is also a great tonic. Now I am seventy-seven, my right knee is beginning to creak as I trundle my trusty steed up Stanmore Hill looking to tilt at windmills in the vicinity of Bushey Heath. I haven’t passed another rider in three years but no matter: retaining my balance on two wheels whilst weaving through traffic is an achievement. Sonia has been threatening to ground me since the day I passed out cycling to work, owing to jetlag, seven years ago, only to be escorted home by two lovely women who stopped to render me assistance. But even she recognizes that my biking makes me less of a grumpy old man than otherwise.

Having more time on my hands has also enabled me to complete my novel: an on/off obsession since 2014. Anyone can be a writer; the trick is to find a literary agent who loves your work sufficiently to take you on board pending a publishing deal. Sadly, I have yet to open that email which commences Dear Mr Cohen, we at Curtis Baron were entranced by your submission…. It seems that a tale of relationships between Jews and others is a little too niche. I persuaded myself that going down the Amazon KDP self-publishing route was the next best option.

Online feedback has been encouraging. As have been the presentations to reading groups where complete strangers have actually paid good money for the privilege of reading the story of a Geordie lass, from a secular background, finding her way into Orthodoxy. But as far as reaching a wider audience is concerned, I have to accept that my marketing strategy requires a reboot. I should live long enough to complete it.

Three years ago, when Sonia tripped over a paving stone and smashed her shoulder to smithereens, I slotted into the role of full-time carer. Helping her to get her confidence back is probably my most worthwhile achievement since my diagnosis. Thirty years of companionship on country walks has kept us strong in the face of mishaps.

Reviewing my activity since 2020, I am not disappointed. I will continue to sing, cycle and write. Our attendance at Edgware and Hendon Reform Synagogue for Kabbalat Shabbat on Friday evening has not wavered. Nor will we neglect visits to those worse afflicted by the process of ageing. An 80-year-old friend fell from a height in the Picos Mountains recently and was airlifted to safety with just four cracked ribs and sternum. He threw a garden party after he got out of hospital to celebrate fifty years of marriage. Together with Sonia we erected a gazebo. Life is good. There are no guarantees that it will remain so. But making the most of it is the best we can do.

The Death of My Father

In my mind’s eye I see you, sat on the ledge smiling in at me, three floors above the traffic that runs along Green Lanes Haringey, roll-up dangling from your lip, window frame on your knees, polishing the glass with a damp shmattah, enjoying a smoke on one of those regular early 1950’s days. You’re in work, cutting smoked salmon for the clientele of Cohen’s (another Cohen, not you) Delicatessen in the Edgware Road, and there are the tips too, which, after the rent is paid, leaves enough for a two-week holiday for the three of us in a boarding house at the seaside.

Through the glass I watch as you pinch the cigarette with your thumb and second finger and move your lips to reassure me: “I’m all right son, I won’t fall.”

And you didn’t fall, did you Dad? You slogged it out in the infantry for four years until they medically downgraded you. Maybe you were cracking up and they saw it coming. You never talk about the War, do you? I desperately want you to be my hero but when I ask you what was the best thing about the army and you tell me it’s when you got a change of underwear, you can understand why I’m disappointed, can’t you? Didn’t you ever fire a Bren gun? Toss a grenade or two? How come you never shot any Germans? (We only found out later that they were Nazis.)

I found this photo (‘10/9/45 – Germany – Morrie’) in the tin box I keep, among the medal ribbons, shaving brushes and the testimonial from the commanding officer of 860 Laundry Bath Platoon: ‘…in sole charge of a Bath House with a small German Staff.’ Why are you smiling dad? Because you’re going home soon, back to your mum (I shuffle the stones on her grave too when I make my annual pilgrimage to Marlow Road)? Or because you just like the whole cleaning shtick? And how small was the German Staff? At six foot in your laundered socks and shoulders like a docker’s, I bet you were bigger than any of them.

Meanwhile we’ve moved to Stamford Hill. On one side the neighbours are a Belgian frum family who lost people in the Holocaust. The sound of the husband’s rants filters through the walls. On the other side are Welsh goyim, a grandmother, a daughter and a grandson. The boy doesn’t have a father; he never came back from the war. My father, the mensch, takes the boy along with us on our trips to watch Arsenal pay football. And we do laugh a lot when you tell Mum we are going to the park, and we end up at the cinema.

In 1957 after you don’t feel well on our two-week seaside break in Weston Super Mare, they take you into Hackney Hospital but before the turn of the year the doctors have decided they can’t do anything more for you and they send you home in your pajamas and dressing gown and you spend the remaining few weeks of your life in bed, in pain. And the last time I can be sure I see you is the morning of the day I take my 11 plus exam in January 1958. Two days later, in the evening, you are gasping out your life. Mum tells me to run round to Dr Rosenthal, three streets away, and ask him to come as soon as possible as Dad is very ill. We don’t have a phone and although there is one by the parade of shops in Dunsmure Road, it’s more reliable to send me. Or maybe she just wants me out of the house.

Getting home, I shut my ears to the sound of you dying in the bedroom two floors above the kitchen where I sit reading Tom Brown’s Schooldays. An uncle and aunt arrive to keep me company, but they merely whisper to each other, so I go on reading. Gradually your gasps grow weaker, until the house falls silent, and Dr Rosenthal departs and then the uncle and aunt depart. And then my mother descends to the kitchen and sits down by my side and gives me the news which I have been careful not to anticipate. On cue, I burst into tears. That night, she and I occupy the single bed in the room adjoining hers. Sleeping beside your corpse is not an option.

The next day, I hand a note to my teacher, Miss Marigold, telling her that I will be off school for a week, and I scurry back to my desk while she reads it. And people come to our house who sit and talk to my mother and cast surreptitious glances in my direction.

But there’s one thing I can do Dad, which you never could, because you never went to cheder or had a bar mitzvah; I can read Hebrew. And it’s just my good fortune that at the New Synagogue, Egerton Road there is a youth minyan, full of boys, older than me, who know how to daven and at their head is a young rabbi, the very rabbi, as luck would have it, who is my cheder teacher. And although I’m only 10, I am uniquely qualified; I am the only mourner amongst them and my duty and privilege is to recite Kaddish every Shabbos.

Except that it turns out that I’m not up it. The young rabbi summons me one evening at cheder and tells me I’m a disgrace and my Hebrew reading is a disgrace, and I should stand outside the class and practice, and only return to the classroom when I am competent.

So, I stand in the corridor, weeping bitter tears of shame. On the walls are mounted photographs of previous generations of cheder pupils. Without exception they look down on me. ‘Ignoramus’ is their verdict, can’t even recite the mourners’ prayer for his own father.’ And it’s your fault, Dad; if you hadn’t gone and died, I wouldn’t be standing here now, would I?

Give me a sign Dad, come to me in a dream, smile at me through the window. You’ve been sitting on that ledge, puffing on the same smoke, for nigh on 70 years. Time is pushing on, the water needs changing and outside, in Green Lanes, evening is drawing in. There’s a chill in the air, and I’m beginning to feel the cold.

It’s My Funeral

Nothing focuses the mind on one’s own mortality like the death of a close friend and a near contemporary. When it’s our turn, with both our sons entrenched as American citizens, who will make the annual visit to shuffle the stones on the spot where my wife and I are interred?

Every autumn, in the month of Ellul, we make the trek on public transport (confession: train and bus journeys evoke a sense of pilgrimage) to stand over our parents’ plots in Rainham and East Ham to recite Kaddish. Six hours and ten changes of transport, with an interlude for a sandwich and a coffee. Inevitably, there are other graves to visit: a sister-in-law in Rainham and at East Ham an entire family, relations of my wife, buried in adjoining unmarked graves, who were wiped out in a V2 rocket attacked in 1944. Except, as we discovered, a couple of years back, a daughter survived, Lillian, who converted to Christianity, and raised her own family. Aleha shalom: peace be upon her too.

But once we are gone, there will be a dearth of visitors. We’ve talked it over and agreed on a woodland burial. The memorial masons will just have to take it on the chin; though with the glut of post war baby boomers reaching the end of their allotted spans, there should be enough work coming in to keep them busy yet a while.

Naturally, to save on cost we’ll be laid to rest on top of each other. The idea takes a bit of getting used to, but it makes complete ecological sense. Everything decomposes in the one plot; the shrouds, the grave markers, and of course, us. Instead of a slab, they can plant a tree, preferably one with the decency to shed its leaves in autumn.

The sexton took my call as the wind whistled round her in the wilds of Cheshunt. She seemed remarkably upbeat, even offering to take a card payment there and then. With prices set to rise, why the hesitation? Nevertheless, I was reluctant for the bill for our funerals to appear on the same credit card statement as the fruit and veg from Sainsburys. Despatching a cheque seemed, somehow, more appropriate.

As for the eulogies: our sons are quite capable of coming up with the salient points; my romance with Arsenal, my wife’s passion for rikudim, Israeli folk dancing. Just so long as they omit the toe-curling bit about us looking down on them. Joke: a rabbi at a funeral admits he never knew the deceased personally and invites those gathered in the prayer hall to say a few words. Silence. Desperate for someone to say something positive about the gentleman who has passed away, he repeats his request. His brother was worse calls out a voice from the back.

I got my cancer diagnosis in June 2020. The surgeon who did the biopsy was also a Cohen. On simchas, we should meet on joyous occasions, I said to him once he had finished with the scalpel. He nodded sympathetically. Thanks to the wonderful staff at the Royal Free, my condition is under control. Although I am realistic enough to appreciate that I have not been given a clean bill of health, the side effects of the drug regime I am on are a small price to pay for survival.

So, still time to select my shiva playlist.

Scrolling through YouTube, I discovered the perfect piece for my final farewell: Shir Shel Yom Chulin: A Poem for a Weekday,[1] words by Rachel Shapira. The Odelyah Berlin performance is hauntingly atmospheric: the voices phrase the poetry beautifully, reflecting the enigma of existence – and there is a cello interlude to die for; hopefully, not literally. But then, it’s not a lyric which I would expect the mourners to sing along with. If I’m to stick with Hebrew, something a little less daunting would be considerate.

Choice number two: the rousing Naomi Shemer anthem Al Kol Eleh[2]sung by 12,000 Israelis, young, old, Ashkenazi, Mizrahi, Ethiopian, accompanied by the Jerusalem Street Orchestra on Israel’s 70th birthday. Over the honey and the bee sting: over all these (Al Kol Eleh) please guard for me my good God. Surely, a suitable replacement as a national anthem if Hatikvah ever falls out of favour. With great instrumentals, and its focus on the faces of the most photogenic amongst the audience, Al Kol Eleh is a reminder of our desperate love for the Land and its inhabitants.

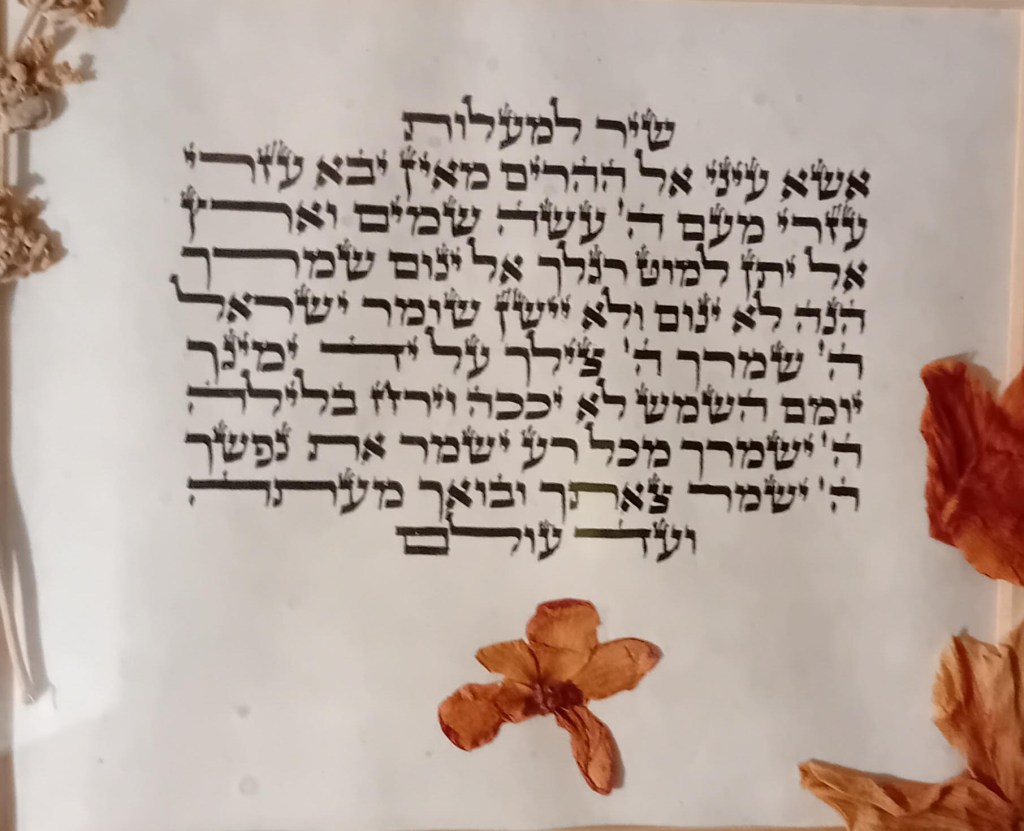

Finally, my all-time favourite: Psalm 121, the Yosef Karduner version[3] – a world away from the churchy tune which usually gets sung at shivas – I raise my eyes to the hills, where my help comes from. Karduner, a Hasid with guitar, belts it out with feeling.The framed text of the psalm, decorated with dried flowers, handwritten by a scribe, has hung on our wall for the past 40 years, a constant presence throughout the ups and downs of our own lives.

A little unfamiliar to most folk; perhaps. But it’s my funeral and I’m entitled to select the music even if it doesn’t conform to what is deemed acceptable at the conventional shiva. I’ll even upload the tracks to my Facebook page and website before I go. That way, I’ll be able to reach out to whoever wants to stay in touch. Buried under a horse chestnut in Cheshunt but forever online. Death, where is thy sting?

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yjLEBdMicIE

[2] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oxzR9Z-kG6Q

[3] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=naOpxmgU2LU

Of Fights, Fringes, Fires and Fumbles on the Fore deck

‘Your schooldays are the best years of your lives,’ we were told. I still retain vivid memories of life as a Grocers’ boy from the late 1950’s to the middle 1960’s, though sadly the team of lads I played football with has been diminished by illness and death.

“He probably only just scraped through,” says my Uncle Jack on hearing of my success in the 11 plus. It’s June 1958 and I am being grilled by Vernon Barkway Pye, headmaster of Hackney Downs Grammar School (popularly known as Grocers), who asks me what books I have read. I practically live in the Stamford Hill public library but can’t recall a single title apart from Biggles Flies East.

After an uncomfortable silence, the headmaster turns to my mother. “If he is awarded a place, you won’t allow his religious education to interfere with his schoolwork, will you?” My mother, a widow of five months, consents, but she is angry with herself and Barkway Pye, ever after. Still, a letter arrives after a few days saying I have been accepted.

“Laurence Cohen,” calls out Mr Vaughan (maths) as the new first year pupils stand in the forecourt waiting to be allocated to their classes. I step forward. So does another, smaller boy. “Who are you?” enquires the maths man. “Lawrence Cohen,” I say, sensing the beginnings of an identity crisis. “Do you spell Laurence with a u or a w?” “W,” I say. “Well, I called Laurence Cohen with a u,” says Vaughan dismissively,” Go back until you hear your name called.” Day one and it’s not looking good.

Actually, I’m being unfair; after a shaky start I find my natural level amongst the lower forms of life; the thoughtfully nominated Y and Z groups, in contrast to the Alpha and A classes where Literature is studied and where Harold Pinter once enjoyed a meeting of minds with the inspirational English teacher, Joe Brearley. And, incredibly, I manage to win a boxing match in my first year. It happens like this:

Stan Gunter, the PE teacher, partners me with a rather short sturdy lad who is broad as I am tall and skinny. We wear boxing gloves, but we don’t wear head guards so being hit repeatedly around the head gives me a keen sense of the way that my brain floats around inside my cranium. I’m all flailing arms and he is all clubbing fists, but somehow Stan gives me the decision.

After the swelling in my frontal lobes has gone down, I figure that my opponent has actually pulled his punches – in the hope that Stan will select us to repeat our evenly matched bout in the finals in front of the whole school. But we are not chosen.

The next year I’m paired with same lad again. I race out of my corner, a dervish on Benzedrine, but this time he pummels me almost senseless. Stan asks me if I want to carry on. I nod dumbly, like a prisoner being offered a blindfold before execution, hoping it will soon be over. And it is: Stan stops the fight a few seconds later.

By the way, Grocers’ boys used to swim without trunks to avoid polluting the school swimming pool (so they tell us). Our dads have omitted to mention that naked pubescent boys are prone to engage in mild homoerotic behaviour. Fortunately, us Jewish lads all wear Tzitzith, fringed undergarments, which go some way to sublimate the Evil Inclination.

It also helps that the school production of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale entertains applications for the female roles from the local girls-only grammar, John Howard. We can stop fooling around with each other and, feigning an interest in Elizabethan drama, start exploring the possibilities of a mutually consensual grope with a Perdita or Hermione. But a fault in the electrical wiring intervenes and Hackney Downs School is incinerated. The magnificent amphitheatre, the venue for the production, where Harold Pinter once played, burns to the ground in 1963, along with the top floor of the main building.

The School is broken up, and its denizens, are sent into exile. Years one to three are billeted in the Victoria Jewish Youth Club in Stamford Hill. We older ones find ourselves in a barren waste land, Wilton Way, a Secondary Modern in Central Hackney reserved for the most lumpen amongst the proletariat. The Grammar School boys, Christian and Jew alike, fear for their safety – but a saviour is at hand, and a Jewish one at that. Bob Z has words with the local hard men, and we are not discomforted.

In this Hackney version of the Purim story, I even have a small speaking part:

One Who Rises Up In Every Generation To Smite Us: “Do you know a kid called Z…..?”

Lawrence with a ‘W’: “Er, yes.”

OWRUIEGTSU: “Tell him we want to see him outside at break.”

Lawrence with a ‘W’: “Er, alright.”

As it happens, many of us identify strongly with the proletariat, although we get a bit panicky when we find ourselves alone with any of them, especially in Mare Street after the pubs have shut. So, it’s no wonder that once we return to our fire-scarred Hackney Downs site, Labour is returned as the boys’ choice, in line with the actual result of the 1964 General Election. And I am the Labour candidate! I have triumphed and am congratulated (through gritted teeth) by Mr Williams, the successor to Barkway Pye, in School Assembly. My fifteen minutes of fame have arrived.

But nothing compares to the fifteen minutes I spend after sundown with Laraine, a golden-haired girl from Plymouth, on the fore deck of the Devonia, a converted troop ship, which ferries parties of school kids around the Baltic on so called ‘Educational’ Cruises. What does she see in me, a lanky fifteen-year-old in with near terminal acne? Really, I don’t have the answer. So, Laraine, if you are out there….

In our final year, 1965, I am convinced that our crusty Economics teacher, L J Marr, is more generous in his assessment of certain boys’ work. There is only one way to find out: I copy out an essay of Alan K’s word for word and submit it as my own. He gets B minus; I get C plus. Vindication! Sadly, Marr knows a bit more about us than I give him credit for: Kaufman gets a place at Cambridge whilst all my university applications are rejected, apart from Bradford Poly which puts me on its waiting list.

Still, I am not disheartened. my seven years at Grocers have not been a complete waste: I have won a fight, I have snogged a girl (admittedly, not on site) and I have played a small part in the struggle to establish socialism in this green and pleasant land.

And some 55 years later, when the distinguished Old Boy, Lord Michael Levy, Baron Levy of Mill Hill, a near contemporary, visits the College where I earn a crust as a humble English lecturer, I contrive to bump into him, and our mutual acquaintance with the School, and its public-school style House system, is renewed – much to the chagrin of the College Senior Management Team. His lordship is ushered away, and Lawrence with a ‘w’ is left considering the vagaries of fame and fortune.

Intimations of Mortality

Where did the time go? How come the years have slipped away so fast? No, not a rewording of a lyric from Fiddler on the Roof, rather the realization of the post 1945 baby boom generation that the end, if not nigh, is approaching with more rapidity than we would care to admit.

The Yom Kippur liturgy asks: ‘what are we, what are our lives?’ Certainly, our good fortune was to be born in the era of the welfare state, a time of full employment and the absence of a major war. Even in the austerity years of our childhood, when food was rationed and bomb damage scarred the urban landscape, no one starved, no one died through lack of basic medicines. The biggest threat to the lives and lungs of us inner city dwellers was the belching smoke from coal burning domestic and industrial chimneys which cause an annual plague of poisonous fogs.

But what of the age-old prejudice, antisemitism? In the 1960’s it was still possible for my college Principal to deny students the right to set up a Jewish Society, reasoning that England was a Christian country. We went ahead and did it anyway. Or the HR manager for the now defunct C&A who confessed to me at a job interview that the company was reluctant to hire Jewish managers as they left after a while, taking with them the experience which they used to benefit their own family firms. I shrugged in sympathy. Then there were the boys who pelted us as we came home from Cheder, but then we played the same lads at football in Christians versus Jews teams at the end of each school term without coming to blows. Antisemitism for those of us who grew up in the Jewish heartlands of Stamford Hill and Hackney was a pale imitation of that suffered by Jews elsewhere.

As a Diaspora community, the fate of Israel hung heavily on our consciousness. As a child I recall listening to BBC radio bulletins which recounted the casualties suffered by Jewish settlements in the Fedayeen raids. On the first day of the Six Day War in 1967, when the fog of battle obscured what was happening on the ground and in the air, we trembled with our not knowing. Others had more faith: an Ethiopian (non-Jewish) College friend, whose emperor, Haille Sellassie, traced his descent from King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, assured me that Israel would enjoy an overwhelming victory. Many of us rushed to sign up as mitnadvim – volunteers. I got as far as the Jewish Agency office before I got cold feet. Arriving in Kibbutz Kfar Giladi long after the fighting was finished, I promptly fell into a perimeter security trench dug to repel Syrian tanks on a first night trip to the loo.

The idealism of 1967 survived the trauma of the 1973 Yom Kippur war. We rejoiced as Begin, for Israel, and Sadat, for Egypt, signed the Camp David Accords in 1978. The promise of a two-state solution filled us with hope. But, with the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin, the interventions in Lebanon and the campaigns against Hamas, and Hezbollah, many of us started to question whether Israel would ever achieve peace on its borders, tranquillity in its homes. The determination of the Jewish settlers of Judea and Samaria, to realize the promises of Holy Writ, was out of kilter with our sensibilities, though we recognized Israel’s non-negotiable right to security. Meanwhile, shortly after Hamas carried out their atrocities on October 7th, our wonderful non-Jewish friends in Southampton invited my wife and I to stay with them if the level of antisemitism in London made us feel threatened.

As British Jews we have flourished: the network of Jewish schools which will ensure the survival of Jewish life well into the middle and late decades of the 21st Century. And the handful of Limmudniks who gathered for their first conference at Carmel College in 1980 must today surely be shaking their grey-haired heads in wonder at the phenomenon they created. And let us never forget the contribution, in the 1970’s, of the 35s women’s group which led the campaign for the right of Soviet Jewry to emigrate.

But while we have leapt to the defence of beleaguered Jews worldwide and distributed money through World Jewish Relief to benefit developing countries and those who have suffered from natural disasters, other communities in the UK have struggled. Who would believe that Jews could ever be the victims of a scandal akin to Windrush? Our communal organisations, refined by 2500 years of Diaspora experience, mirror the state’s welfare agencies and speak to Government in defence of our interests. Surely, we should be working harder with less advantaged groups in society to develop their relations with Government through their own community institutions.

And then there is our wider responsibility for the welfare of planet Earth and its inhabitants. Our insatiable need to consume has denuded the world of natural resources and removed the habitats of countless species. Our love of air travel has doubled down on carbon emissions. We are the generation who have bequeathed to our children and grandchildren the consequences of global warming. Certainly, there is a recognition of the need for Tikkun Olam, Repairing the World, but little evidence that many of us take it seriously enough in the conduct of our daily lives. My contribution has been to book a woodland burial.

Approaching the end of my eighth decade, I fear for the world our grandchildren will inherit. As a species we benefit from a surfeit of cleverness, epitomised by the gadgets at our disposal and our embrace of artificial intelligence, but what we lack is the wisdom to recognize that our sojourn (lovely English word) in this garden of Eden is short and our uncomprehending selfishness will blight the lives of generations yet unborn. We read in Ethics of the Fathers: the work is great, the labourers are sluggish. No, we may never finish the task, but neither are we free to excuse ourselves from working towards its completion. May the promise of a messianic world be speedily fulfilled. This is the hope that we cling to.