A selection from my published writing

Why it’s a Mitzvah to wear a funny hat at Purim

Every year, immediately before Purim, my rabbi enjoins his congregation to attend the reading of the Megillah, intoning magisterially, “Remember to wear a funny hat. Don’t forget.” For him, this is the supreme Mitzvah; visiting the sick, accompanying the dead, attending the bride, don’t even come close.

I am wracked by the need to discover the origins of this commandment. Finally, with the benefit of a scholarship from Bar Ilan University and the blessing of my wife (‘take five years, take ten years; only don’t talk to me while I’m watching Master Chef’), I embark on the momentous task of assembling the evidence.

I begin with the Mishnah, where the dispute sets the School of Hillel against the School of Shammai. The enigmatic Hillelite statement: “The hat is not the issue” (Ha-Kova Hoo Lo Ha-Iqar) seems to have provoked unusually acrimonious clashes between the students of the two houses and resulted in broken heads.

Later, in the Babylonian Talmud, the veil is lifted. The majority hold that the hat needs to be intrinsically funny, i.e. the mere sight of it would cause the observer to titter, even if it were not on the head of the wearer (my italics).

By contrast, the minority led by Rabbi Yaakov argue (and this is surely Hillel’s point) that context is everything. For example I might don a policeman’s helmet together with a burglar’s vest composed of broad horizontal hoops. This would induce helpless laughter in the observer. Granted, it would help if the observer was observing the other supreme Purim Mitzvah: to get legless.

So divided are the rabbis that they declare ‘Teyku’; ‘let the decision be made by Moshiach when he comes’.

The dispute re-emerges with renewed vigour in the twelfth century when the Ramban takes exception to the section of Mishneh Torah where the author, the Rambam – without recourse to the sources – states that the Halakha is with Rabbi Yaakov. The Ramban immediately issues a Herem (an edict of excommunication) against the Rambam.

Confusion descends when the Rambam points out that the Ramban has spelt his name (the Rambam’s) with a Nun instead of a Mem and has consequently excommunicated himself (the Ramban). The Ramban is later to be found wandering distractedly through the streets of Cordoba whistling the Eton Boating Song.

Closer to our own time we know that the enigma of the funny hat obsessed Sigmund Freud. Freud would go on to write a study of the Book of Esther (‘The King Who Mistook His Wife For A Hat’) in which he speculates that Ahasuerus married Esther, not because she was the most beautiful woman in his empire, but rather because she reminded him of his mother’s beanie.

My work begins to receive recognition from scholars from a multiplicity of disciplines and I am deluged with material. Ruth Chapeau, an historian of the American Labor movement in Newark, New Jersey draws my attention to the Lower East Side Novelty Hat Workers strike of 1901 which prompted Rabbi Nossin Shtreimel of the Adath to issue an edict against the purchase of hats produced by blackleg operatives brought in to break the morale of the unionized labor force

The strain of following up so many loose strands starts to take its toll. My professor, Dr Naftali Tembel, fears for my sanity and insists that I return home to visit my wife. Now, on the verge of publishing my magnum opus, I learn that she has left me for the arms of Morris Lefkowitz, the eponymous owner of S Lefkowitz and Son, Distributors of Ladies Millinery Trimmings.

My rabbi adjures me not to yield to bitterness. I have, he reassures me, succeeded in un-entangling one of the thorniest Halakhic problems of our epoch. “Take time out for yourself,” he urges, “visit some internet dating sites.” So here I am, sitting in the bar of the Tel Aviv Hilton waiting for one Trilby O’Ferrall to walk through the door. I suspect it’s a pseudonym. The only O’Ferrall I know is a Sadie…

https://www.thejc.com/lets-talk/all/why-its-a-mitzvah-to-wear-a-funny-hat-at-purim-1.53161

March 14 2014

Of feasts, fasts and far-off Finsbury Park

For some it’s Rehov Ben Yehuda or the Champs Elysees, for others the Nevsky Prospekt or the Unter den Linden. But for me, born 1947, the issue of a late returning soldier and a never-say-die spinster, delivered in the Royal Northern Hospital, succoured in rented rooms above an ironmongers shop in Green Lanes, Harringay, initiated some few years later into the cult of football at Highbury, the stretch of the Seven Sisters Road between Holloway Road and Manor House was the highway that linked all the meaningful locations in my early life.

Growing up as an only child in the early 1950’s, on the same latitude as Stamford Hill, but to all intents and purposes, a galaxy away, I inhabit a world of horse drawn milk carts, bomb sites and pea-souper fogs where stout aunts pull on my cheeks as a sign of affection leaving my eyes watering with pain. I am able to work out for myself that Kanine a Horror are words of endearment rather than a curse on a rabid dog, but often adults say things which leave me confused and speechless.

“Lawrence, tell us about your Feasts and Fasts.” Forty-one pairs of English and Cypriot eyes turn on the only Jewish child in the class at South Harringay Junior School. At the age of seven I am having difficulty working out what I am supposed to say. Miss Diprose, sensitive to my bewilderment, attempts to tease an answer out of me: “I mean, do you have a Fast and then a Feast,” she smiles encouragingly, “Or is it the other way round?”

I know for a fact that the adults in my family fast on one day a year (not my dad; religion has somehow passed him by) but, as far as I am concerned, feasts exist only in the pages of Billy Bunter stories where Billy and his public school chums hold midnight feasts in the dormitories of Grey Friars School. I have no idea what she is talking about. Miss Diprose moves tactfully on. But I feel that I have let her down.

If Feasts are part of being Jewish, why hasn’t anyone mentioned them at Cheder? I try to fathom this mystery as the 29 bus carries me along Seven Sisters Road to the Cheder in Finsbury Park where I learn to read Hebrew from a primer called Rashis Daas.

Somehow, I have forgotten, my cupple, my head covering. Before I can ask him about Feasts my teacher waves me in the direction of the head teacher’s office where a group of senior students are being taught. I knock and enter: “I haven’t got a cupple”.

The head teacher looks round at his group, smiles and turns to me. “No cupple? What shall we put on his head – a boot?” The seniors all now turn to smile at me. What an ignoramus, their looks seem to say, don’t you know to bring a cupple to Cheder? Don’t you know that the Christians call our Paysach, Shavuous and Succos Feasts, that Paysach follows the Fast of the First Born, and the Fast of Esther precedes Purim, but otherwise there is no correlation?

I shuffle about on the spot for a minute, unsure of what to do next as they have gone on with their lesson and as no one is paying me any attention anyway, unnoticed, I slip out of the room. I can’t return to my class bare headed, so I walk back up Blackstock Road to the Seven Sisters Road and get the bus home.

Night is falling. On an otherwise deserted upper deck of a Number 29 a man asks me if I like football. Nervous about remaining tight lipped with any more adults that day I say yes, which is the truthful answer, and he invites me to his house where he has a football which I can have if I am interested. Somehow we establish that the ball in question is a rugby ball and, seeing a way to decline his offer without offending him, I explain that soccer is my interest. He doesn’t seem that bothered but I stare purposefully out of the window for the rest of the journey just in case.

My Auntie Celie – not my real aunt: we share rooms with her and her family – on the other hand is incandescent: “Why did you come back early?” I don’t have the words to explain. “Just wait till your mother gets back from work,” she mutters darkly.

I wait apprehensively but there is no telling off from my mum and, as nobody mentions it at Cheder the next time I go, I feel that I have got off lightly.

At the other end of the Seven Sisters Road is my Auntie’s Ladies Foundation shop – Goodhardt of 518 Holloway Road – where I go at least once a week, usually on a Saturday, with my mum to visit her older sister, Yetta. A few doors away stands the Royal Northern Hospital where I entered the world. The nurses who patronise my aunt’s shop speak the dialects of the 32 Irish counties and despite the daily routine of dealing with death, none of them would dream of speaking of the dead without appending a God Rest His Soul to the name of the deceased.

Sat in the parlour drafting designs for warships on an endless supply of flattened nylon stocking boxes (each pair comes in its own slim, stiff, cardboard container), I listen with one ear as Yetta and my mum gossip on the other side of the curtain that separates shop from home: “Manny, God Dressed His Soul, would have been disgusted!”

Laying aside my blueprint for a battleship that will be the pride of the Royal Navy in the next war, I try to work out what soul dressing consists of. The Window Dresser would appear to hold the key. Every so often he materializes at my Auntie’s and, stripping the displays bare, begins the elaborate process (in his socks) of creating a fresh and even more enticing montage of brassieres, girdles, corsets, slips and nylon stockings, replete with price tags and product labels. The act of correcting a minor fault after the main work has been accomplished is a trial of nerve and balance worthy of crossing Niagara Falls on a tightrope.

In a flash of enlightenment I perceive that souls are kitted out in some celestial Savile Row by the Divine Window Dresser in preparation for their passage into the shop of heaven.

In Auntie’s Irish/Yiddish lexicon for speaking about the deceased, Manny, God Dressed His Soul has to compete with Manny, Over Show Lem (Alav HaShalom: Peace Be Upon Him). This is less impenetrable. For Manny, the Show is indeed Over. But who or what is Lem apart from a character in the children’s radio serial, Journey into Space? (“Lemmie, Lemmie, are you there?” asks an anxious Dan Dare over the walkie-talkie into the infinite silence of space, the hairs bristling on the back of my neck while I shiver in anticipation of next week’s episode.)

Anyway, Auntie Yetta is a great one for peppering her speech with references to the divine as she supervises her ladies hosiery universe: Thank God, Please God, God Forbid! (either literally: God forbid it will rain this afternoon, or sarcastically; God forbid he should remember to phone his mother occasionally) and the one that I particularly admire: If the Almighty spares me….. .

Auntie always utters this in a tone that suggests that, although she is prepared to submit to the Divine Will, if the worst comes to the worst, the Angel of Death will know that he has been in a fight. “If the Almighty spares me I’ll be at my granddaughter’s Chupah.” No contest. What Deity worth His salt would fail to give the nod to Auntie Yetta, if only on points? Not only is she at the Chupah (Wedding) but the Angel prudently stays his hand long enough for her to rejoice in the birth of her great grandchildren, Kanine a Horror.

Now that world has been swept away. The Seven Sisters Road still runs majestically through North London but the Almighty has taken to Himself both my aunt, my mother, and the Irish nurses at the Royal Northern hospital, itself absorbed into the Whittington. He has dressed the souls of Miss Diprose who was doubtless mortified that she had embarrassed me and the head teacher of the Finsbury Park Cheder, who was in truth a kindly man. He has dressed the soul of the man on the bus who drew back from enticing a small child to his home. Aleihem HaShalom – Peace be upon them.

And one day, though I pray He will tarry, He will dress mine.

https://www.thejc.com/news/world/of-feasts-fasts-and-far-off-finsbury-park-1.56258

August 21 2014

Dear Dad …… Your Father’s Day letters

In my mind’s eye I see you, sitting on the ledge smiling in at me, three floors above the traffic that runs along Green Lanes, Harringay, roll-up dangling from your lip, window frame on your knees, polishing the glass with a damp shmattah, enjoying a smoke on one of those regular early 1950s days between being demobbed and dying.

“I’m all right son, I won’t fall.”

I found this photo (“10/9/45 – Germany – Morrie) today in your box among the medal ribbons, shaving brushes and the testimonial from the commanding officer of 860 Laundry Bath Platoon: “… in sole charge of a Bath House with a small German Staff.” Why are you smiling, Dad? Because you’re going home soon, back to your mum (I shuffle the stones on her grave every year when I visit yours)? Or because you just like keeping things clean?

Give me a sign, Dad, come to me in a dream, smile at me through a window. You’ve been gone 53 years; time is pushing on, the water needs changing and the Staff wants to get home.

Lawrence

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2011/jun/18/your-fathers-day-letters

How I faced the challenges of coming out as an LGBT father

The signs were there early on. One Hanukah, around 1982, when the child was three or four, I bought her the best dolls house in the toyshop. After some initial curiosity it was discarded and sat gathering dust until we eventually gave it away. Later came the insistence on wearing football shorts as her foundation garment of choice, even under the pretty velvety dress she wore to her brother’s Bar Mitzvah. And she was the best at climbing ropes in her primary school.

As for me, I was happy to have a tomboy for a daughter. Going in for a tackle in an eleven a side football game (the other 21 were boys) indicated a spiritedness rather than a misplaced sense of identity. So what? The child continued to exhibit a love of furry stuffed animals and enjoyed going on play dates and sleepovers with girls. In time though, on learning from their own daughters that our child was speaking of her ambition to become a boy, the mothers put their foot down and the invitations ceased. Then did we pause to wonder.

And when the child started Secondary School there began the daily ritual, on returning home each day, of changing from the compulsory girls’ uniform into boys’ clothes. But the thing about this school – Mill Hill County High – was that the teachers were understanding and most kids who went there accepted the child for who she was and there was no overt bullying, and most important of all, the child made a friend who was on his way to being gay and they were there to support each other.

But then puberty reared its head and with it came breasts and periods and while the breasts could be flattened with tightly bound bandages, the other thing led to a sorrow for the awful physical reality of her gender which left the child wailing loudly in her room, and my wife I powerless in the face of her, and our own, despair.

Gender Dysphoria. We learned the name for it on our trips to St George’s Hospital in Tooting which has a unit for young people who believe – whether by nature or nurture we do not know – that they were born into the wrong body. So began a period of therapy for the child, initially fruitless as the she was reluctant to talk, but thereafter, with the help of a gifted therapist, progressively rewarding for her sense of self.

Eventually the time came for the young person to go to university, attending from day one as Adam, the name given to the first human creature before it was separated into its female and male personas. Of course, our Adam, unlike the one in the Bible, had to rely on the breast bandages and a regular dose of sustanon to provide the testosterone to deepen his voice and grown hair on his cheeks. But it worked, and Adam, as he has been ever since that first day at Central St Martins in October 1996, is the son we know and love.

Graphic Design is not the easiest trade to make a living at. But it’s a level playing field out there and although transgender designers have no edge in the job market it’s not exactly a hindrance either, particularly as most people either don’t know or don’t particularly care about what bits you’ve got or haven’t got under your jumper and knickers, unless they fancy you, of course. And it helped that lots of media and design folk were (and still are) queer like Adam. And even he wasn’t sure that he fancied girls more than boys – but that’s about sexuality, not gender.

But how do you tell friends and family that your daughter has become your son? The truth is most of them had already sussed it. The friends who remain our friends gave us unfailing support. The revelation were my elderly cousins, born a full generation before me in the 1920’s when gay was a word with totally different connotations, who have always given Adam hesed (loving kindness) and never failed to show a concern for his well-being. And then there is Adam’s brother, now a rabbi in the USA, who chose Adam to be best man at his Chupah.

Two years ago Adam and his partner entered into a Civil Partnership. Although the ceremony took place at Stoke Newington Town Hall, itself a favoured Chupah venue, the reception was in a local gastro pub. The best man was the gay friend from Mill Hill County High. The bride (female) who isn’t Jewish but was working for a Synagogue at the time, and the groom (female to male) wore matching suits. The bride’s sister flew in from New York with her Jewish boyfriend, the groom’s brother and sister in law, the rabbi and the rebbitzen, from Las Vegas. The toilets were unisex. To get to the bar you had to navigate the lesbians. So, not dissimilar from any other function you have ever been to!

Now, we are losing him. Adam and his wife (they are now married) are emigrating to the USA where Annette was born. Earlier this year we did a hike in the Lake District for charity. It was first period of days we had been alone together in 20 years. I could have spoken of the pain I had once felt, but you know, we had terrific fun, him scampering over the fells, me losing my balance attempting to keep up. I may have fallen a few times but I got up. I was with my son, I was with my friend.

As a parent you want your kids to grow up in your image and after your likeness. Mostly it happens. Sometimes it doesn’t. And when it doesn’t you just have to make the best of it.

November 5 2015

A tribute to Solly, lost but in our hearts

A yellowing page torn from the JC of July 16th 1943 lists the casualties; those killed in action and on active service, the wounded, the missing and the prisoners of war. At the foot of the page there is a photo of my cousin, Sylvia, Corporal S Fenton, from the Mile End Road in the uniform of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force who has been Mentioned in Dispatches and listed in the King’s Birthday Honours. Seventy years later I interviewed Sylvia and recorded her remarkable story on video, so her great grandchildren should know her, now that she too has passed.

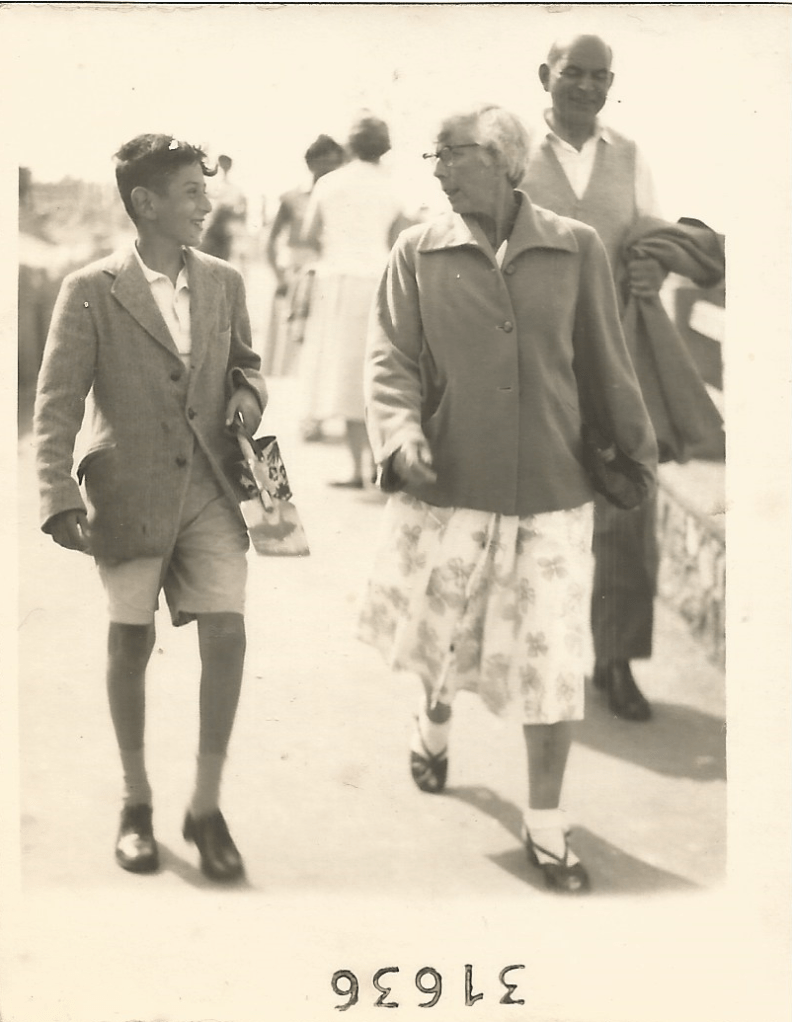

But what of the fallen? For those us born to the survivors, there are no memories, only names, mentioned in passing at Seder tables, or images in a family album. We never knew them, and even those who did; they are getting fewer and frailer with each year that passes. How to honour the Jews who served in the British armed forces and were lost? Here is one story for Remembrance Day, pieced together from recollections of a fast receding past, from a letter, from a photograph, from a visit to a grave, and, more recently, from an internet search.

At a hearing convened by the London Beth Din at the end of World War Two, a man and a woman come before a rabbinic court to perform the ritual of halitzah. The man testifies that he is not willing to take the childless widow of his deceased brother for his wife. In response, the woman removes the shoe from the man’s left foot, spits into it and makes the declaration: thus shall be done to the man who will not build up his brother’s house. She is now free to marry whom she chooses.In reality, the hearing is a formality; the man already has a wife and a child of his own and there is another on the way.

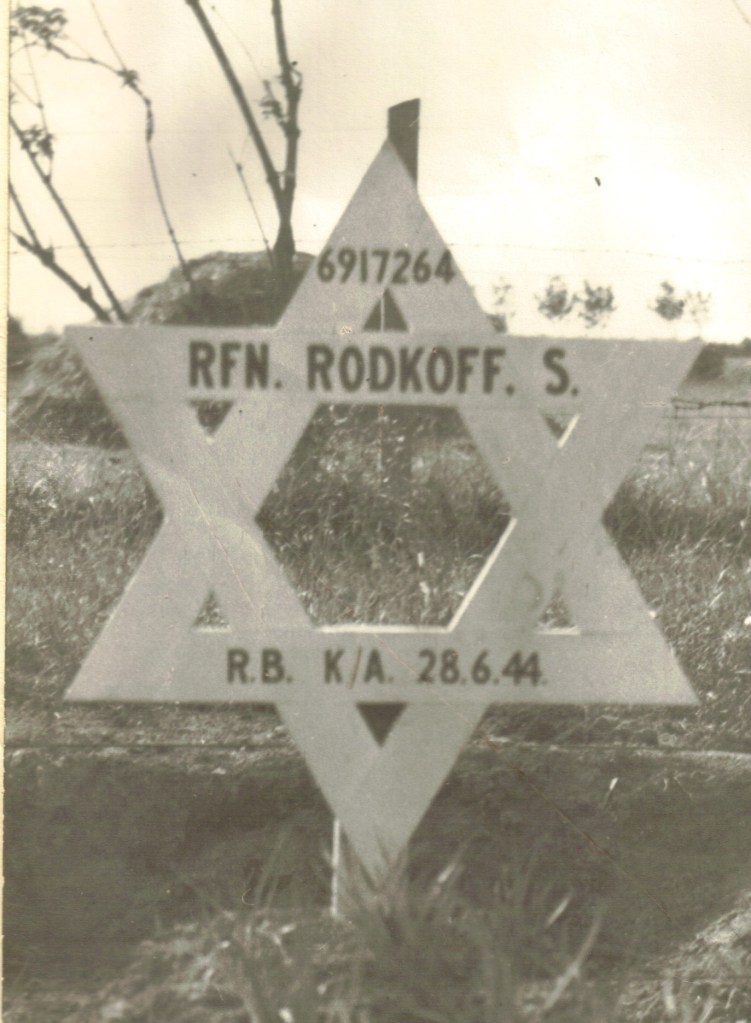

The man is my father-in-law to be, Myer Rodkoff. The woman is Sally, nee Sarah Bloom, the widow of Soloman Rodkoff. In the year that marks the 75th anniversary of his death, in Normandy on 7 Tammuz 5704, on 28 June 1944, this is his tribute.

According to his sister, Rene, Solly was a spieler, a gambler, thrown out of the family’s Jubilee Street tenement by his father, on more than one occasion. Though Rene and her siblings were born and raised in poverty, the good name of the family was at stake and Solly was only readmitted on his promise to take up a respectable trade. But even a wife couldn’t keep him at home when the call came to join the fight against Fascism. Enlisting, as a volunteer, rather than waiting to be conscripted, Solly, now Rifleman Rodkoff, was assigned to the sharp end of the Allied invasion force: 8th Rifle Brigade, part of the 11th Armoured Division, charged with leading the break-out from the D Day Normandy beaches.

We can never know, precisely, the circumstances of Solly’s death. A letter from the Senior Jewish Chaplain, Second Army, dated 30th August 1944, provides some details; a small measure of comfort to his grieving parents:

Dear Mr and Mrs Rodkoff

…….. First of all, let me express to you my heartfelt condolences and deepest sympathy in this tragic loss which you have been called upon to bear. I can only pray that the knowledge that he died at the Front, in the cause of the Liberation of Europe and of our people, will help to assuage your keen sorrow.

Your son’s death affected the whole unit deeply. In the morning he had an amazing escape, a shell hitting his vehicle and passing through the engine, without touching him. He was congratulated on all sides at his good fortune, and in the afternoon he was wounded and evacuated. It was not realized how seriously wounded he was by his unit, but he died the same day at the Field Ambulance and was buried by the chaplain to the 2nd Fife and Forfar Yeomanry who was present.

I received all these particulars from his unit, when I visited it at Myer’s request, and I can therefore speak directly of the great esteem in which he was held by his unit, as a fearless and gallant soldier, and a good comrade.

May the Almighty send you His Comfort and Consolation ……

According to a memoir[1] by a fellow soldier, it was German Tiger Tanks which caused heavy casualties among 13 Platoon; four men were killed, including Solly, and there were numerous wounded in the fight to throw the enemy off of Hill 112, soon to become a killing field for an entire British division.

Coincidentally[2] I discover that Solly was nick-named Russia by his comrades; a recognition of his parentage and the respect which the British squaddies had for the Red Army which was winning the war in the east. In fact, the Rodkoffs were from the Ukrainian town of Kamenetz Podolsk; they just fancied themselves as Russians.

Solly’s death was not the only tribulation suffered by his family in 1944. In October, Solly’s half-sister, Bessie, was killed along with her husband and son in a V2 missile attack on London. For them there is no memorial; only entries in the registers of birth, marriage and death.

It wasn’t until the late 1980’s that we found Solly. Together with my wife, Solly’s niece, and our two young children, we drove the A413 from Caen to the Banneville-La-Campagne British military cemetery. There, in the furthest row, lies Solly. A photograph taken shortly after his internment shows a temporary memorial; a wooden Magen David bearing his name, rank and number, the initials KA (killed in action) and the date of his death. Now a standard Commonwealth War Graves Commission headstone marks his last resting place.

Among the fallen, there is a scattering of other Jewish graves: Cyril Litwak, Emanuel Mossack, Mendle Rottman, Vitalis Weingreen, Anthony Ekstein, Harry Garfunkle, Joseph Abrahams, Arthur Marks. They served in units ranging from the Royal Armoured Corps to the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders. They hailed from a variety of locations: Manchester, Hull, the London contingent from Bow, Dalston, Mile End and the Upper Clapton Road.

Of Solly, little remains apart from the stone; an entry in the cemetery records, a photograph of him in uniform taken with his brother Myer, a letter of consolation. There should have been a child: you see his widow, Sally, who spat in the shoe of her brother-in-law, to manifest her contempt at his refusal to build up his brother’s house, was pregnant at the time of her husband’s death, but she miscarried and the families lost touch.

My guess is that the halitzah ceremony weighed heavily on Myer. He had failed to talk his younger brother out of enlisting in the infantry; cannon fodder in his own words. So, when in the following year a girl was born to his wife, Nancy, he named his daughter Sonia. Sonia, my wife, a living memorial to her uncle Solly. On this Remembrance Day: Zichrono Livrachah; his memory for a blessing.

[1] With the Eighth Rifle Brigade from Normandy to the Baltic, Don Gillate

[2] http://ww2talk.com/index.php?threads/h-company-8th-rifle-brigade-11th-armoured-division.60217/

https://www.thejc.com/life-and-culture/all/a-tribute-to-solly-lost-but-in-our-hearts-1.494744

The Jewish Chronicle December 30 2019

The friends who cared

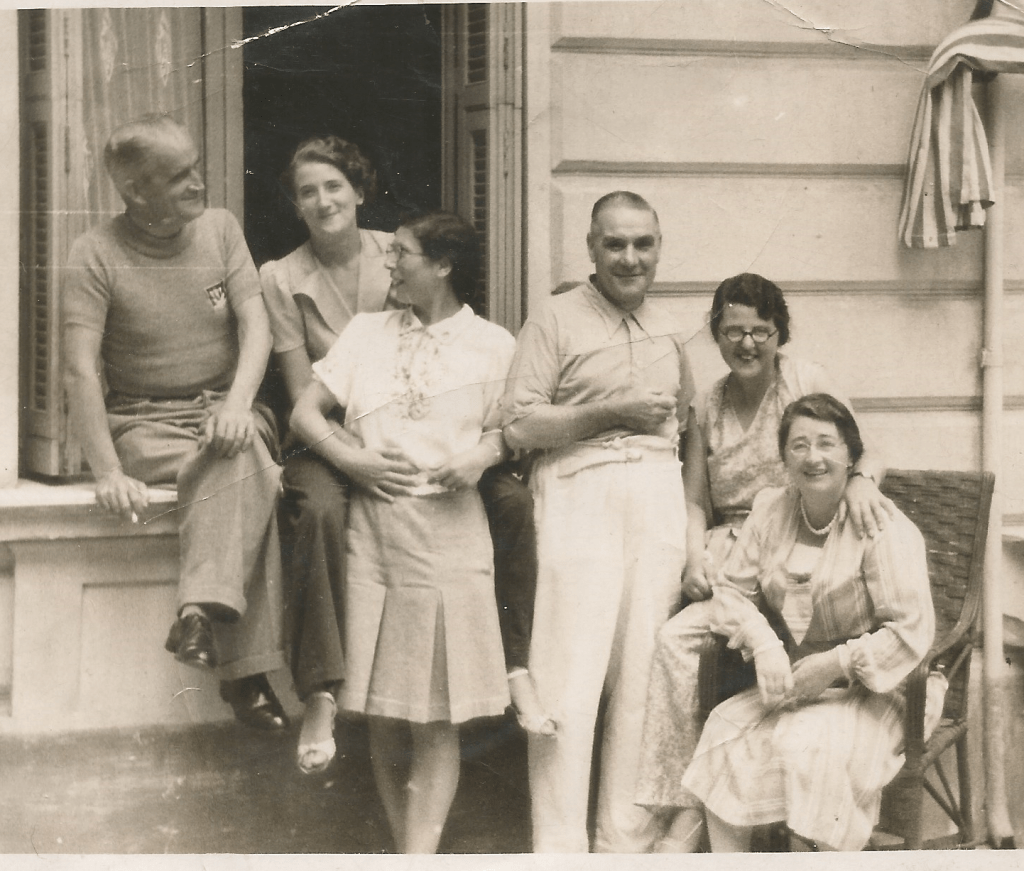

Let us take a closer look at this group photograph from the 1930’s. Nineteen young women in their 30’s and 40’s and three men smile as a photographer from the World Jewish Press Photographic Agency, headquartered in Fleet Street, clicks the shutter. The occasion is clearly a significant one: everyone is formally dressed, with a couple of tiaras and some floral adornment in evidence. The men, one or two spouses and the regulation guy from head office, are incidental to the proceedings. Seated in the front row are the movers and shakers decorated with sashes of office. Among them, the third woman on the left, bespectacled, in a black dress with a lace top, clutching a small object (an evening bag?) is my mother, Rachel Finestein. She wears the collar of her past presidency. Unlike her brothers who anglicised their name to Fenton, she would remain Finestein for another ten years or so until, at the age of 42, she was introduced to Maurice Cohen, aged 39, with whom she, later, had a child. Me.

The gathering is to celebrate some event in the calendar of the Princess of Wales Lodge No 25 (Ladies) affiliated to the order of Achei Brith (Brothers of the Covenant) and Shield of Abraham, a mutual self-help alliance of friendly societies which acted as a safety net in times of sickness before the establishment of the Welfare State. So, who are the women behind the smiles?

I can only contribute my own recollections, now fast fading, of my mother and her friends. I knew several of them as ‘aunties’, women who never married, largely due to the shortage of men after the carnage of the Great War. They were the progeny of immigrants in the East End of London, who on leaving school at the age of fourteen or thereabouts, seized the opportunity to avoid the drudgery of the garment factories by learning shorthand and typing and progressing to clerical work. My mother, Rachel, was typical. She joined a City company, newly qualified, in May 1918 and only retired from the same firm in 1993 when her health began to fail. She retained her friendship with the girls from the Lodge throughout her life. A memory of my childhood is being taken to tea with her pals at the Regent Palace Hotel off Piccadilly Circus in the mid 1950’s. Very posh, although the orchestra and the cucumber sandwiches impressed me less than the marble urinals in the basement.

As young unmarried women with a degree of financial independence, they also went on holidays abroad, unimaginable to the majority of East Enders: Norwegian Fjords, an excursion down the Rhine. Another photo, with an inscription in French on the back shows Rachel and her friend, Sarah Harris, posing in an entente cordiale with some Gallic chums, looking like they are having the time of their lives.

By contrast, running the Lodge was a serious undertaking. The friendly society depended on the scrupulous honesty of its elected honorary officers in collecting subscriptions and distributing benefits to members in times of sickness and financial need. Socially, the Lodge also played a huge part in the lives of these women. And they were not uninvolved in the febrile political atmosphere of the 1930’s either. My mother described to me how she was delegated to take shorthand notes at an anti-fascist meeting – just in case there was a Metropolitan Police undercover agent present who might present a false account of the proceedings to his superiors.

Devoted to duty, Rachel, like her friends, took her quiet, unassailable spirit into wartime. Holding down her clerical job by day, by night she was a volunteer St John Ambulance nurse in the London Hospital in the heart of the East End. She always claimed that being selected to march in the St John contingent in the 1946 Victory Parade was reward for her efforts in collecting donations around the East End tenements. But I have my doubts.

Researching this article in a publication of the Jewish Historical Society[1], I made a discovery which brought tears to my eyes: a photograph of her own Presidential Collar, the one which she is seen wearing in the group photograph, identified in the archives of the United Jewish Friendly Society[2] as: ‘worn by sister R Finestein 1933-4’. She would have been delighted to know that her badge of office was preserved on the internet for posterity.

Remarkable women, living in a remarkable era, whose sense of community and regard for each other ensured that life would still be liveable even in the hardest of times.

[1] See: The Jewish Friendly Societies of London 1793-1993. R P Kalman and Raymond Kalman. Included in Jewish Historical Studies Vol 33.

[2] The archives of the United Jewish Friendly Society and its predecessors are held by the University of Southampton

https://www.thejc.com/family-and-education/all/the-friends-who-cared-1.505797

The Jewish Chronicle August 19 2020